Last September I decided that I wanted to learn how to build a VRChat world. I had never made a VR project before, but I’ve been working in and around interactive entertainment since before the turn of the millennium, so I have Opinions, and plenty of them.

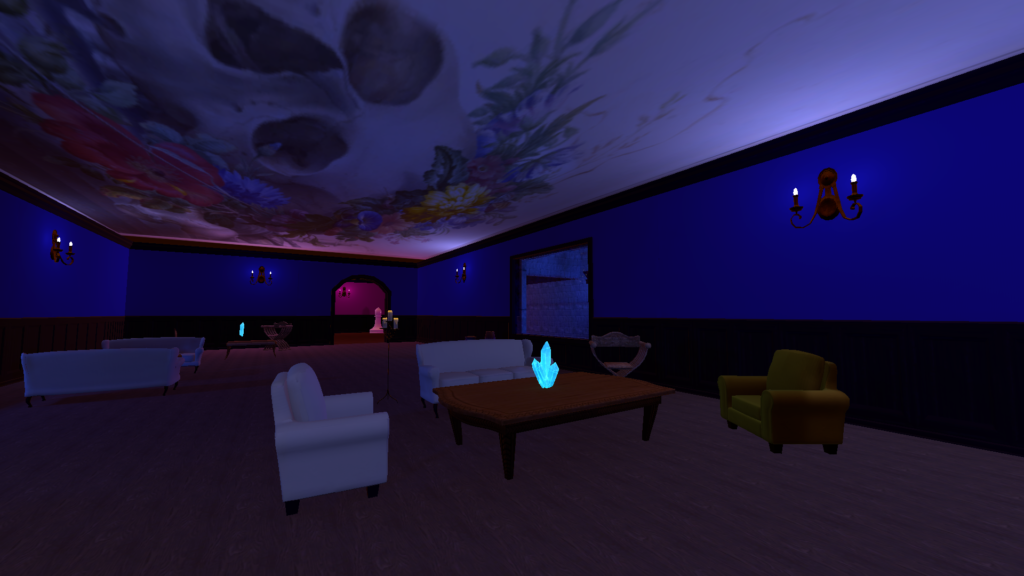

I wasn’t sure what sort of world I wanted to build; I have notes and outlines for various ideas I’ve had over time, but none of them seemed quite right. And then, by happenstance, I reread The Masque of the Red Death, by Edgar Allan Poe, in particular his description of the prince’s imperial suite. The image of that series of color-themed rooms, lit by giant braziers, was arresting to me.

Also, at this particular moment in history, what could be a more appropriate inspiration for a VR world than a story about locking yourself up to hide from a plague and then throwing a big party with all your friends?

So I made a world. And having made one, I have some thoughts about what I tried to do, what went well, what did not go well, and what I regret. I thought I’d share them.

Aesthetic Principles

There were four primary things that I wanted to accomplish with my design:

- First, I wanted to create a social space suitable for a party, with interesting places to hang out, and a mix of large spaces for the main party with smaller spaces for more private conversation.

- Second, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, I believe in the power of size in VR, and I wanted to use scale as a tool to create a certain gravity.

- Third, I wanted to employ the principle I identified in my favorite 3DOF experiences that there should be nowhere wrong to look.

- And fourth, I wanted to build it out of free assets, which was partly about an affection for free culture and partly about me being a cheapskate.

Things That Went Well

To begin with, I finished it, and it works, neither of which was a given. It is sort of stunning looking back just how little I knew about anything. I’d done some Unity tutorials, but I’d never shipped anything real. I’m proud of myself for sticking with it through … a variety of setbacks. About which more anon.

I also think overall, Revel is a pretty neat world. There are lots of spaces to explore, lots of places to hang out with friends, and lots of odd things to look at. (I want to take a moment to note that the Inexorable Orb *predates* the “orb contemplation” meme. I got there first, damn it.)

I think I had some successes with scale. The frescoes on the ceilings of the imperial suite are really cool, and the aforementioned Inexorable Orb works pretty well. And I think I achieved some good effects with various objects that are a little uncanny on account of being unduly large.

I succeeded in using only free assets, which was at times an interesting challenge. I had to search in all sorts of places to find things I wanted, which was an adventure in and of itself.

Things That Went Less Well

My biggest misstep was that I had not fully internalized the difference between assets that are designed for standalone PC games, and assets that are optimized for VR. As a result, a lot of the assets I picked turned out to be enormous, and I wound up having to pare a lot of things back to get the world size down to something manageable. My initial build was two and a half times as big as the final version is, and the final version is still larger than I would like it to be.

For this reason, I basically failed in my goal to fill the visual field with interesting things; I just didn’t have the polygon budget for it. (It was also a challenge finding enough free and interesting assets to fill the space to the extent that I did.) However, on reflection, I think filling the visual field is a less meaningful aesthetic principle in a six-degrees-of-freedom setting. In a 360-degree film, things are happening on a fixed timeline; every moment the audience is looking at something uninteresting is a wasted moment. But a VRChat world has as much time as the audience is willing to give it; as long as there’s enough interesting stuff in the space to keep people looking around, it’s OK if there are some relatively blank spaces. (This may be less true of VRChat experiences on rails, like Magic Heist.)

Relatively sparsely filled areas were helpful in another respect, namely my objective of creating spaces for private conversations. I had not realized in advance that VRChat does not have audio occlusion, and so being on the other side of a wall from someone makes absolutely no difference in terms of being able to hear their conversation. However, the abbey is large enough that the storerooms are sufficiently far from the rooms of the imperial suite that normal falloff will actually give you some privacy.

Although I had some successes with scale, it was much harder than I anticipated, for a couple of reasons. First, scale turns out to be very hard to judge in the Unity editor. Things regularly seem much larger or smaller in VR than they looked in the editor window. I had to do a fairly significant rebuild when I realized I had made scale decisions that looked completely ridiculous in headset. (Another lesson: test in headset early and often.) Second, my commitment to free assets (and my limited ability to create assets from scratch) made some scale efforts difficult; scaling objects up from what they were supposed to be sometimes works really well, but sometimes it just looks weird.

Regrets…I’ve Had A Few

A principle I believe is very useful in almost all parts of life is “Begin with the end in mind.” I…did not employ that here. I did a lot by the seat of my pants, in ways that were often ill-planned, and that caused me a lot of extra work. (If we ever happen to be in the same room after I’ve had a few, ask me about the floors, and why I am a dumbass.)

I also did not think through some of the implications of my own ideas, and so despite my belief in the power of sound, I searched for music late in the process. I wish I had started that early and allowed my soundtrack to inform more of my decisions along the way.

That said, both of these issues stem from the fact that I just did not know what I was doing, and was not in a position to solve problems before I knew I had them. So I feel OK about it. But I’ll do it differently next time.